Born in Chatham, Kent in 1940, Zandra Rhodes is a fashion and textile designer and founder of the Fashion and Textile Museum in London. Known for her bold, outlandish use of colours and prints, she has dressed royalty and pop culture’s most famous, from Princess Diana to Debbie Harry. Rhodes has appeared in Absolutely Fabulous, and won a Daytime Emmy award for costume design in 1979. Her memoir, Iconic, has just been published.

Makeup artists are good at making you blossom, and my good friend Richard Sharah was wonderful at this. I am in a dress I designed after a trip I took across America in 1974 in a Volkswagen camper. It was gorgeous; and inspired my Cactus Cowboy collection. A wonderful period of my life.I first started dyeing my hair in 1973. When Vidal Sassoon brought out coloured wigs I gave them a try, but they pinched my head. Instead I realised I could colour it myself: it’s been green – like the colour of dried grass – pink and blue. I dyed it brown just once but it lasted two weeks as I found the experience so horribly embarrassing. Pink doesn’t require too much maintenance, so that’s why it’s stayed that colour.

My mum, Beatrice, didn’t dress like anyone else. She had a passion for style and once worked as a pattern cutter for the couture brand, House of Worth. She would collect me from school dressed to the nines. I’d say: “Please don’t come looking different from all the other mothers.” She always did. Once she sprayed her hair silver and then got a lacquer to set it. We were on a train and she kept saying: “My head keeps stinging.” It turns out she’d covered her head in fly spray.

She was a lecturer at the Medway College of Art, so I’d get to try on dramatic clothes there, but wouldn’t dare wearing them in front of the other children at my school. I didn’t have many friends when I was young – I was a very boring child; always hard at work. Everyone in our house was like that; always busy, in a rush. We weren’t a family who relaxed.Being called Zandra was always an embarrassment. Teachers thought it was a mistake in their register. They’d say: “There’s no such name!” Nevertheless, I loved school. Even when I was at home I was always painting or illustrating something. While Mum was at her sewing machine, I’d be upstairs designing clothes for my doll, Jacqueline. The first was a multicoloured dress, hand stitched with striped bias binding. It was important that Jacqueline was always nicely presented.

In the early 1960s, I studied at the Royal College of Art, and had been encouraged by my lecturers to try to sell my designs. The feedback I got from buyers was that my style was too bold compared with everything else at the time. I was making bright, colourful designs, an early print interpretation of pop art. I didn’t take the setbacks personally. My amazing mother always told me I would make it.

The turning point in my life was when I went to America with my collection and showed it to [fashion editor] Diana Vreeland at American Vogue. She raved about it; the tide was turning in a new direction. After that, my whole life changed.

Much of the 1970s were spent in New York, promoting my designs. I didn’t have a social life in London – I was always in my studio – so to be suddenly part of this wild social scene was totally new. Where once I’d been so disciplined, I was at all-night raves or mad discos. I’d probably get in at 1am, but that was still quite late for me, especially when I was up early working.

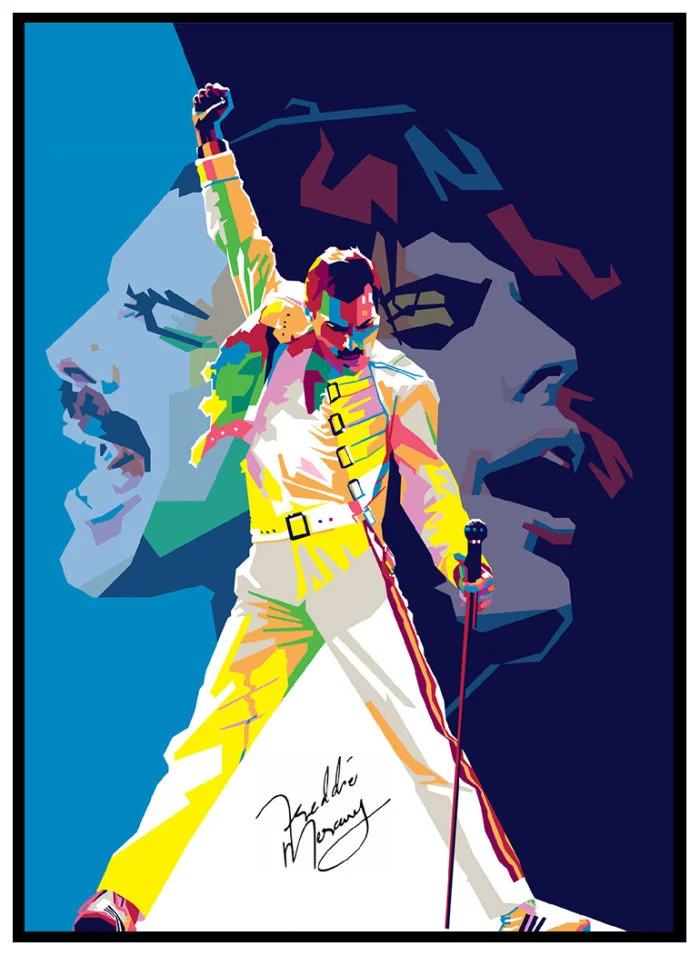

I’d never heard of Queen, but Freddie was very shy and lovely; not like an unapproachable rock god. He told me he wanted to look like a showman

It was an amazing experience to be at the Factory. Andy Warhol would be in his office, filled with Karl Lagerfeld’s extravagant furniture, and poets and artists were always milling around. I’d wear very dramatic makeup and had streaked hair with feathers tied on to the ends; a scarf around my head. It was around this time when Richard took me to his friend, the interior designer Angelo Donghia’s studio. He saw me and said: “Well if you dress this exotically, I’d love to see your work.” He bought my textile designs, which I hadn’t been selling in the UK. It was like riding high on a wave.

I must have been in my mid-30s when Diana Ross threatened to crush me under her garage door. I had been introduced to her previously while in London, and wearing my best clothes. A year later I was in LA, and driving along with a friend, when she said: “Look, that’s Diana Ross getting out of a car into her house. You know her! Go and say hello!” Diana took one look at this vision of a woman with green hair, like some kind of hippy, and said: “If you come one step nearer I will shut this door down on you.” I rushed back into the car. Friends woke me up the next day to tell me that Diana had realised it was me, found out where I was staying, and had rung in the middle of the night to say she wanted to come over for breakfast. She arrived and had coffee and a snack. It was a very funny experience.My meeting with Freddie Mercury was quite wonderful. It was 1974, and he and Brian May were due to visit me in my studio. I’d never heard of Queen, but Freddie was very shy and lovely; not like an unapproachable rock god. He told me he wanted to look like a showman, and I picked out a white pleated bridal top that I thought may suit him. It was made in heavy ivory silk and had giant butterfly sleeves. I went on to make a custom design of the top and he wore it when Queen performed later that year.While I was never intimidated by any star, I did have the awful experience of dressing Zsa Zsa Gabor. She was like a kitten when you put the clothes on her, but once the men disappeared out of the room she’d say: “I hate this dress.” I met her many years later and asked if she’d given all my dresses away to her daughter and she said: “No, darling, I love them so much.” I thought: “What about what you put me through? You had my staff in tears.” It was all very strange.

Right at the beginning of Covid, my great friend, the artist Andrew Logan was in my home. He said: “Zandy, you never do yoga. Why don’t you try?” We lay on the floor and he told me to breathe deeply. I did as he said, and felt as if my stomach was full, even though I hadn’t eaten all day. It turned out I had a 13.5cm growth in my bile duct and I was given six months to live. I told three people about my cancer; my main concern was that I wouldn’t be able to get all of my work done.About nine months later, the growth disappeared. I still have treatment every few weeks; and I don’t breathe as well as I used to. Other than that, nothing has changed. I like to think I’ve still got a touch of exotic about me, although I don’t wear my own dress designs often. When I am in the studio I am in a pair of old trousers, an old T-shirt, maybe a brooch. I don’t want distractions; to rip or get paint on something beautiful. I just want to get back to work.

This is what we’re up against

Teams of lawyers from the rich and powerful trying to stop us publishing stories they don’t want you to see.

Lobby groups with opaque funding who are determined to undermine facts about the climate emergency and other established science.

Authoritarian states with no regard for the freedom of the press.

Bad actors spreading disinformation online to undermine democracy.

***

But we have something powerful on our side.

We’ve got you.

The Guardian is funded by readers, like you in Nepal, and the only person who decides what we publish is our editor.

If you want to join us in our mission to share independent, global journalism to the world, we’d love to have you on side.