Unlike the sanitised character in the new film Bohemian Rhapsody, the Queen frontman was debauched, outrageous – and proud. We celebrate a rock legend in tight shorts, leather and leotards.

Bohemian Rhapsody is a film that suffered from a difficult gestation. It was announced in 2010 but, in the intervening eight years, everyone from the lead actor to the screenwriter to the director either bailed or was replaced, in some cases several times. Freddie Mercury was first to be played by Sacha Baron Cohen, then Ben Whishaw, although it’s hard to see how either could have done a better job than the actor the role eventually went to, Rami Malek, whose incredible performance is the film’s one unequivocal triumph.You can see why they pressed on with its making. For one thing, few artists have been so hawkish in posthumously extending their brand as Queen: since Mercury’s death in 1991, there have been jukebox musicals, umpteen archive releases and documentaries, as well as attempts to reboot the band without him. For another, Mercury’s story is clearly one worth telling. If anything, he seems a more remarkable figure in hindsight than at the height of his career.The child of Parsi parents, who formed his first band at school in Mumbai, Mercury was an Asian frontman at a time when Asian visibility in rock was virtually nil and racism was overt (intriguingly, the guitarist in Mercury’s Bombay school band was Derrick Branche, the actor who went on to appear as Gupte in the ITV comedy Only When I Laugh). Island Records boasted an Anglo-Indian prog band called Quintessence, but there was certainly no other Asian rock star on Mercury’s scale. He was a gay man who, while never coming out publicly, put his sexuality front and centre in his performances and songwriting, apparently without his audience realising what he was doing.In his autobiography Head On, Julian Cope recounts the experience of supporting Queen at Milton Keynes Bowl in 1982, as part of the Teardrop Explodes, and being showered with homophobic abuse by their fans. “[They] shouted, ‘Fuck off, you queer!’ at me,” recalled an incredulous Cope. “Wow, they dig Monsieur Freddie and they call me queer. So much for the workings of the average mind.”

Bohemian Rhapsody isn’t bad on the issue of Mercury’s race, a subject usually ignored or dismissed as beside the point in the story of Queen. We see Mercury facing down racist abuse while working as a baggage handler at Heathrow and from an audience member at an early gig. But its depiction of his sexuality is more troubling. It’s a film that seems to view the fact that Mercury was gay as little short of a tragedy. His homosexuality leaves him lonely, unable to share his bandmates’ domestic happiness as they settle down into marriage and parenthood. It drives a musical wedge between the band and their frontman, whose ideas for songs and styles are increasingly founded on his experiences in gay clubs and viewed as antithetical to the spirit of the band.

You watch the film and think: ‘God – imagine being in a band with this bunch of prigs’

It also seems to give him a taste for hedonism that makes him unreliable and unprofessional: according to the film, the rest of Queen seem to have spent the late 70s and 80s tutting and rolling their eyes at Mercury’s behaviour before demurely excusing themselves from whatever deranged bacchanal their singer was leading the charge at and going to bed early. Anyone with a passing interest in the band knows this is nonsense. A reporter from the US magazine Circus who attended the legendarily debauched launch party for their 1978 album Jazz noted with surprise: “Brian May seems to be the true organiser of the night’s carnival.” Yet watching the film, you think: “God, imagine being in a band at the height of the most sybaritic decade in rock with this bunch of prigs.”The film’s villain, meanwhile, is unequivocally Mercury’s personal manager, Paul Prenter, a hugely controversial figure in the Queen story, not least because he sold stories about Mercury’s sex life to the Sun while the singer was dying of Aids (Prenter himself died of the disease a few months before Mercury did). Here, Prenter is a devious gay man who, among his compound wrongs and manipulations, lures Mercury into a twilight world of drugs, orgies and S&M clubs, and thus ultimately to his death.

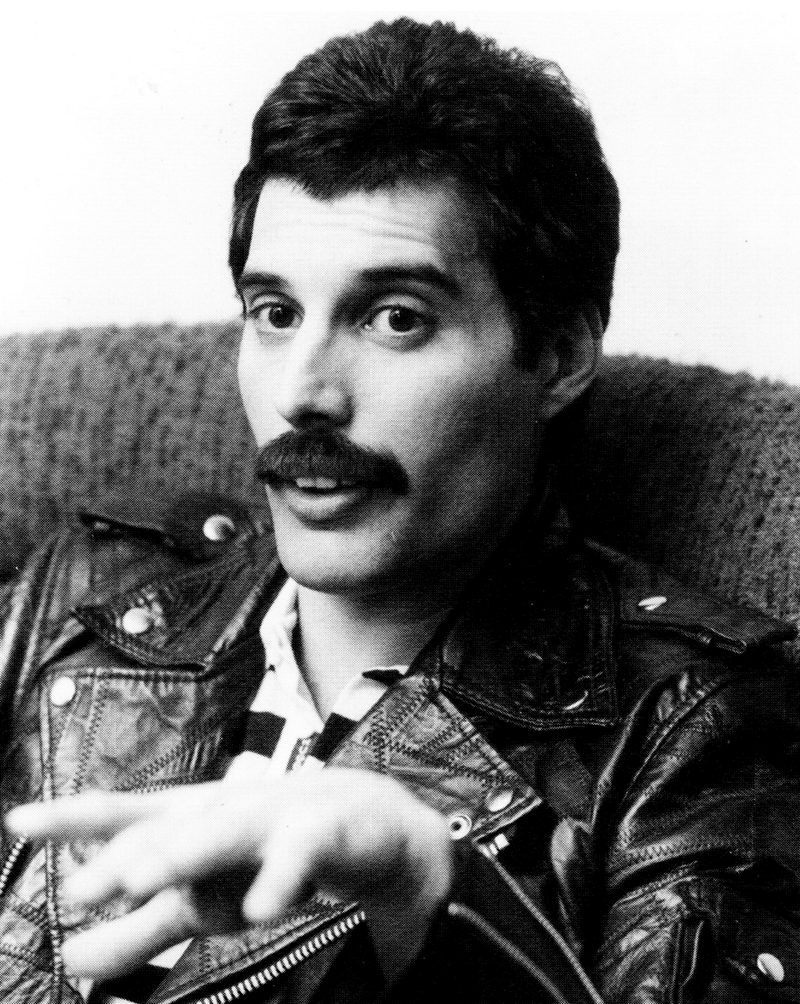

It goes without saying that in virtually every other account of his life, Mercury does not come across as a man who needed a great deal of luring where sex and drugs were concerned. But then Bohemian Rhapsody is a film that plays so fast and loose with the truth, it ends up seeming faintly ridiculous: you start out nitpicking about minor chronological errors (one Queen obsessive took to social media to protest that the kind of reel-to-reel tape seen in the recording of Bohemian Rhapsody wasn’t in production in 1975) and end up with your jaw on the floor during a deranged final sequence that posits that Mercury found true love, came out to – and reconciled with – his parents, then played Live Aid on the same day.Perhaps a certain ridiculousness is perfectly fitting – few bands have so revelled in and owned their own piquant OTTness – but the depiction of Mercury’s sexuality seems unnecessarily reductive. There’s no mention of the debt Queen effectively owed to Mercury’s queerness, which gave them everything from their name to their image. With the greatest of respect to the band’s other members, when you think of Queen, you think of Mercury got up in full leather, dressed like a ballet dancer, naked except for a pair of tiny shorts, or swishing his way through Killer Queen on Top of the Pops. There’s no mention of the impact it had on his performances, despite the compelling argument that it took an outrageous gay man to convincingly sell confections as lavish and preposterous as those Queen kept coming up with.And there’s no mention of the impact of his queerness on his songwriting, beyond the admittedly intriguing implication that the lyrics of Love of My Life and Bohemian Rhapsody might have been fuelled by anguish over his sexuality. You don’t have to delve deep into semantics to find other examples, although you can if you want. Simon Reynolds’ 2016 book Shock and Awe: Glam Rock and Its Legacy makes a convincing case that 1974’s The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke has less to do with the painting of the same name by Richard Dadd than it has to do with “a sex life kept hidden from the public”. Reynolds also draws links between the sound of Bohemian Rhapsody and Wayne Koestenbaum’s study of opera’s allure to gay men, The Queen’s Throat.

But Mercury didn’t usually deal in covert metaphor. He wrote songs that had his sexuality proudly emblazoned across them, from Get Down Make Love to Good Old Fashioned Lover Boy. Amid the huffing and eye-rolling about Mercury’s behaviour, there’s no room in Bohemian Rhapsody for the fact that what may be Queen’s greatest song of all – the astonishing Don’t Stop Me Now – was a direct product of his hedonism and promiscuity: an unrepentant, joyous, utterly irresistible paean to gay pleasure-seeking. You find yourself wondering if its title might not have been aimed at his censorious bandmates.Nor does the film address the obvious delight Mercury took at hiding in plain sight, which remains the most mind-boggling aspect of his career, as audacious in its own way as Queen’s multilayered, more-is-more productions. No rock star in history had as much fun exploiting the public’s apparent inability to cotton on to what was in front of their eyes, something that had to do with the tenor of the times (this was an era in which Elton John could release All the Nasties, a song literally about coming out, without any comment whatsoever).But it may also have been linked to the kind of audience Queen attracted. In Bohemian Rhapsody, the band give a prospective manager a grand speech about their appeal to freaks and outsiders – but that really wasn’t the crowd they drew. Look at the legendary televised Christmas Eve concert from 1975. This is not a band performing before an audience of makeup-sporting aesthetes in Biba’s Rainbow Room at the height of glam. It’s a band playing Hammersmith Odeon to a hard-rock crowd, the kind of people who might have gone to see Uriah Heep or Deep Purple, and who clearly couldn’t conceive of their idols being anything other than straight.

For an encore, Mercury comes on stage in a kimono, which he gradually strips off while singing Hey Big Spender. No one seems to raise an eyebrow. There was the occasional snippy remark in the music press. A notorious 1977 NME profile was headlined “IS THIS MAN A PRAT?” – but these days, it reads less like the wounding character assassination it purported to be than the work of a self-important journalist being made mincemeat of by Mercury’s acid wit. The writer refers to him as a “bitch” but that is it.

Presumably emboldened, Mercury pushed it further and further. By 1980, he was dressing exactly like a denizen of the kind of gay clubs he frequented: muscled, moustachioed, and in tight-fitting jeans and T-shirt. In America at least, this caused ructions. The standard line is that Queen scuppered their own career in the US by dressing in drag for the video of 1984’s I Want to Break Free, but four years earlier on the tour that followed the release of The Game, fans threw razors on stage in an apparent attempt to get Mercury to shave off the moustache, to look less gay. In Rolling Stone magazine, bassist John Deacon as good as admitted that Mercury’s appearance was alienating a US audience that was traditionally prickly about homosexuality. “Some of us hate it,” he said in 1981. “But that’s him and you can’t stop him.”It’s a him that the film studiously ignores in favour of presenting Mercury’s story as a morality tale. That may be how the surviving members of Queen see it: the charitable interpretation is that their take is coloured by lasting grief at his loss. But it sells Mercury – and Queen – short. You only have to listen to their albums or watch live footage to know the truth was far more complicated and interesting.But perhaps Mercury wouldn’t have cared. “I’m not going to be an Eva Perón,” he once said. “I don’t want to go down in history worried about, ‘My god, I hope they realise that, after I’m dead, I’ve created something or I was something.’ I’ve been having fun.”

Bohemian Rhapsody is out now.

• This article was amended on 25 October 2018 to reflect the fact that Derrick Branche played Gupte in Only When I Laugh, not Mr Gupta in Mind Your Language.